Karen Pugh-Clarke

MSc, BSc (Hons) RN.

Clinical Nurse Specialist for CKD at the Royal Stoke University Hospital

Stoke-on-Trent, England, UK

k.pugh-clarke@keele.ac.uk

7.0 Living with Home Haemodialysis

Learning Outcomes

- Outline the positive attributes of home haemodialysis when compared to conventional centre-based haemodialysis

- Acknowledge the psychosocial impact of home haemodialysis for both the patient and care partner

- List the three principal intensive home haemodialysis regimens and discuss the relative attributes of each schedule

Introduction

For individuals with end-stage renal disease (ESRD), a move from centre-based haemodialysis (CHD) to home haemodialysis (HHD) may be life transforming. In addition to promoting self-care, and ultimately independence, HHD is associated with several favorable clinical outcomes in terms of dialysis adequacy, survival, and quality of life1,22. Nonetheless, the decision to dialyse at home is irrefutably the preserve of the patient, based on self-assessment of the advantages and disadvantages of this treatment modality. Such assessment is profoundly influenced by personal beliefs, values, and expectations, which are fundamental to final decision-making. Prior to a definitive decision, the global impact of HHD on the self and potential carers requires scrupulous consideration. The focus of this chapter is to provide an overview of living with HHD, and, in doing so, will address some of the perceived controversies. Issues pertaining to the psychological, sociological, and economic aspects of HHD will be considered, with a view to providing a positive foundation on which to base decision-making.

7.1 Frequency of dialysis

Conventional CHD comprises three dialysis sessions per week, for four hours per session. Whilst this regimen fulfils the function of renal replacement therapy, in that it sustains life, studies indicate that alternative schedules, such as intensive home haemodialysis (IHHD), have the potential to enhance patient outcomes.

IHHD is defined as home haemodialysis with an increase in dialysis frequency (days/week) and/or session length above a standard CHD schedule1. In accordance with Tennankore et al. (2014)1, there are three predominant IHHD regimens (Table 1).

| Principal IHHD regimens1 | ||

|---|---|---|

| Regimen | Dialysis frequency | Session length |

| Short-daily haemodialysis | 5 or more sessions per week | 2.5-3 hours |

| Long haemodialysis | 3-4 times per week | ≥ 5.5 hours |

| Long-frequent haemodialysis | 5 or more sessions per week | ≥ 5.5 hours |

Short-daily haemodialysis is characterised by an increase in dialysis frequency and a decrease in session length. Research suggests that, when compared to standard CHD, short-daily haemodialysis may be associated with improved fluid volume management, decreased left ventricular mass index, and reduced inflammatory markers2. Long and long-frequent haemodialysis are both typified by session lengths of five-and-a-half hours or more, with the latter, as the term denotes, also involving an increase in dialysis frequency. Both long and longfrequent haemodialysis may be provided overnight while a patient sleeps1, and are related to improved pregnancy outcomes3,4,5, tighter blood pressure control6, and increased survival7,26.

A major advantage of IHHD in general is its flexibility. Patients are no longer subjected to the rigidity of CHD, as evident in the following patient testimonial from Peter, 47 years old, on short-daily haemodialysis for one year:

“I dialysed at the main hospital haemodialysis unit for the first two years after I developed kidney failure. Although the doctors and the nursing staff were great, I found that the schedule was really inflexible. My haemodialysis slots were Tuesdays, Thursdays, and Saturdays at 5.30pm. This meant that if I had a work commitment in the evenings (I work part-time in sales), or a parents’ evening at my daughter’s school, I had to try and change my dialysis slot, which sometimes was not possible.”

Peter obviously values the flexibility that IHHD has afforded, which has, in his own words, enhanced his health-related quality of life:

“As long as I do the required [dialysis] hours, I can fit my dialysis around my life. No more inconvenient, rigid schedules which made me miss things that I wanted to do. I feel that finally, after two years, I have my life back.”

Hence, for patients like Peter, IHHD is advantageous over CHD, in that it facilitates continuation in employment or other activities and maintains a semblance of normality.

7.2 Pregnancy

Chronic kidney disease (CKD) is associated with endocrine dysfunction, which has a negative impact on fertility. Decreased kidney function leads to dysregulation of the pituitary-hypothalamic axis1, resulting in testosterone deficiency, impaired spermatogenesis, and erectile dysfunction in males8, and irregularities of the menstrual cycle and amenorrhea in females9.

Pregnancy in females with ESRD on dialysis has always been considered a challenge10. Irrefutably, dialysis is associated with low conception rates and poor pregnancy outcomes, including spontaneous abortion, premature delivery, and low gestational weight1. Nonetheless, in recent years, pregnancy outcomes have improved10, which reflects the more intense management of patients with ESRD who become pregnant3.

In addition to the optimisation of nutritional status, and stringent maternal and fetal monitoring, IHHD is associated with favorable pregnancy outcomes. Barua et al. (2008)3 found that conversion from CHD to nocturnal HHD (7−8 hours, 5−7 nights per week) improved conception rate, and resulted in six live births (at a mature gestational age) in a cohort of five patients. More recently, Brahmbhatt et al. (2016)4 observed a successful pregnancy in a patient receiving short daily low-volume lactate-based dialysate HHD (10−26 hours of dialysis per week [depending on stage of gestation]) and KIHDNEy cohort reported other cases in Europe which are pending publication.

7.3 The psychosocial aspects of Home Haemodialysis

ESRD and its management with dialysis therapy introduces significant psychosocial stressors and adaptive demands11. Nevertheless, the impact of performing haemodialysis at home brings with it specific issues and challenges, which will now be addressed in greater detail.

According to Bennett et al.12, HHD is far more that a medical treatment: it is, in fact, a lifestyle. Not only does HHD have profound implications for patients, it also influences the lives of those around.

7.3.1 Patient perspectives

Depression is commonly manifested by patients with ESRD13, with an estimated prevalence of 20% to 30%14. This is inevitably a consequence of multifarious factors, such as perceived helplessness, hopelessness, and loss of the self. However, studies denote that patients on HHD experience lower levels of depression when compared to their counterparts on CHD15,16. Although the reasons for this difference are not yet fully understood, Suzuki et al. (2014)16 propose that the improved sleep quality and energy attributed to HHD may have the potential to reduce depressive symptoms. Irrespective of this difference, Bennett et al. (2015)12 advocate that patients on HHD should be formally assessed for symptoms of depression. Such assessment should be undertaken on a periodic basis, in order to identify the subtle onset of symptoms and instigate treatment strategies accordingly.

Patients undergoing HHD may experience psychological issues not generally encountered in patients on CHD. One such issue is that of isolation. Tong et al. (2013)17 investigated the beliefs and expectations of patients and caregivers with respect to HHD. Whilst HHD was generally evaluated positively, isolation from social and peer support emerged as a negative consequence.

In response to this finding, the authors advocate a number of strategies to minimise isolation, including peer group support, Internet-based support, and individual (one-to-one) counselling. The value of peer support is apparent in the following patient testimonial from Anthony, 57 years old, on home haemodialysis for three years:

“The thing that I missed most when I started dialysing at home was the company of the other patients on the unit. I really missed the camaraderie and banter. When I spoke to my nurse about this, she asked if she could put me in touch with a local support group for people who dialysed at home. Although the idea did not appeal to me in the beginning, I agreed and made contact with them. It’s been one of the best things that I have ever done. Me and the other patients meet regularly away from the hospital, and are able to support each other through the challenges of home dialysis. I don’t feel isolated anymore.”

Bennett et al. (2015)12 also recommend the introduction of “buddy” systems to HHD programmes. Buddy systems enable established patients to be paired with patients new to HHD, as a means by which to provide support through the unique patient-to-patient experience.

7.3.2 Care partner perspectives

Patients should be encouraged to manage their treatment at home as they will feel more in control of their life, but a trained care partner is required. Care partners may be a spouse, partner, family member (e.g. parent or sibling), or friend, and have various levels of involvement in the patient’s care. Some care partners may take full responsibility for all patient’s care, performing all aspects of HHD. Other care partners may only have a limited involvement in the HHD treatment such as cannulating an arterio-venous fistula, and removing the needles postdialysis, or assisting in case of issue.

Whatever the degree of participation, care partners are susceptible to a multitude of psychosocial stressors. These include loss of income, social isolation, fatigue, distress, depression, and poor physical health18. Combined with an overwhelming sense of responsibility, this may predispose to care partner burnout, with withdrawal from this treatment modality being a potential consequence.

The HHD team are in a unique position to identify the early signs of isolation, poor partner communication, and partner-patient friction, and instigate strategies to minimise care partner burden12. Such strategies encompass:

- Encouraging the maximum degree of patient independence for self-care.

- Providing respite care to relieve care partners.

- Developing peer support networks for home dialysis partners.

Proactive supervision of patients and care partners is fundamental to the success of HHD programmes, as evident in the following two accounts.

Sylvia, 63 years old, care partner to her husband Michael for 18 months.

“When we [the care partner and her husband] first went home, I was terrified that I was going to do something wrong. I felt quite overwhelmed by the level of responsibility that I had. I’m not a medical person! However, with the help of our dialysis nurse, we soon got into a routine, and I became much more confident at setting up the machine and needling his [her husband’s] fistula.”

George, 72 years old, care partner to his wife Alice for one year.

“I was fine in the beginning, but after seven months of being a full-time carer and dialysis partner, I began to feel the strain. I started snapping at my wife, but felt really guilty afterwards. We were lucky because our nurse spotted this immediately, and suggested that we access the respite care service. Carers visited three times every day, and a respite nurse came in to do the dialysis. I was able to take a two-week break, and visit my family in London. I came back feeling refreshed, and resumed my care partner role. I will definitely be doing it again in the future.”

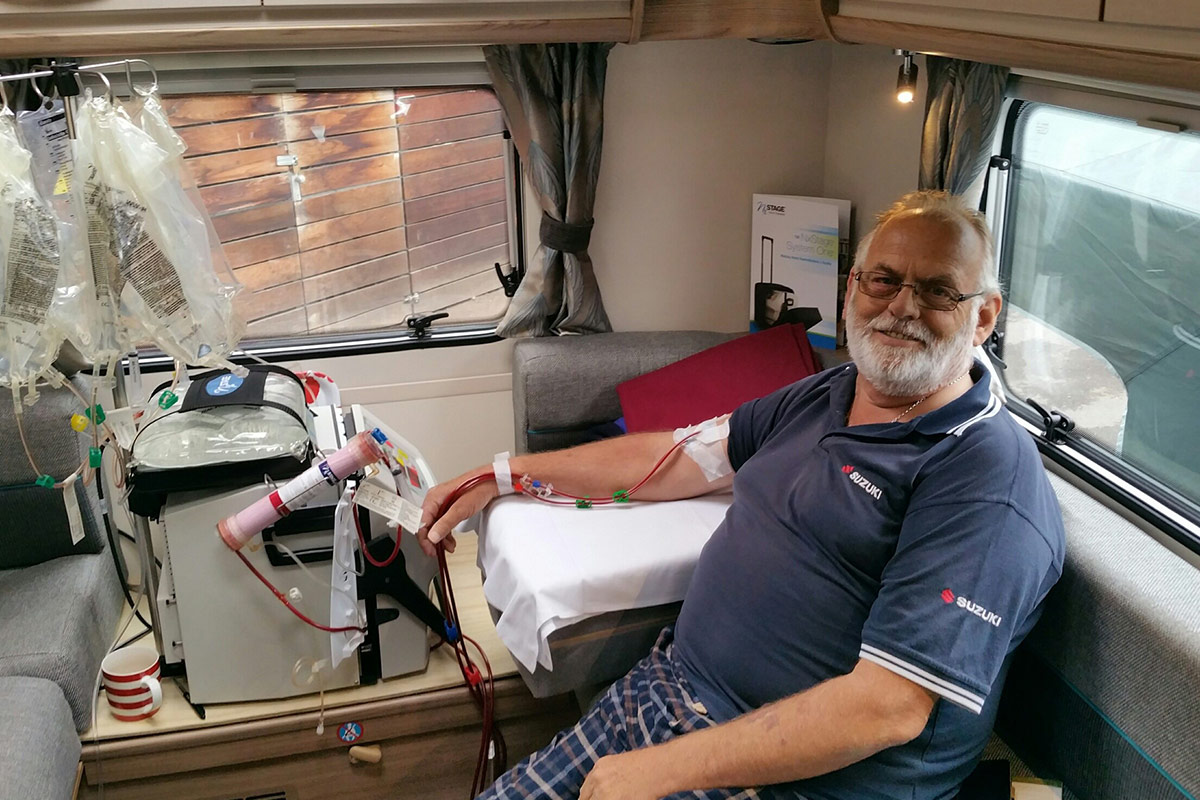

7.4 Travel and holidays

The ability to travel and organise holidays are important aspects of many patients’ lives, and may strongly influence the choice of treatment modality. Whilst dialysis away from home is associated with an increased risk of infection, anaemia, and inflammatory response19. Assisting and encouraging HHD patients to enjoy a holiday may provide them with a sense of normality. Moreover, holidays may have a positive impact on health-related quality of life, and keep patients on HHD longer12.

Kathryn, 53 years old, on home haemodialysis for two years.

“Home haemodialysis has transformed my life as a kidney patient. No more battling with the traffic and the weather to travel to the unit, and no more waiting for the nursing staff to put me on and take me off the machine. I can dialyse in the comfort of my home in the knowledge that help is only a phone call away.”

Nurses caring for patients on HHD have the capacity to endorse travel dialysis. Stratagems to facilitate holiday dialysis may comprise:

- Providing patients with detailed information on holiday and required medical documentation.

- Assisting patients to identify suitable dialysis centres at their destinations of choice.

- Encouraging patients to plan their holidays well in advance.

- Ensuring that the required blood test results are readily available (e.g. up-to-date Hepatitis B, C and HIV status).

- Stipulating that patients have appropriate travel insurance.

- Verifying that patients have adequate supplies of medication with suitable storage facilities (e.g. cool bags for erythropoiesis stimulating agents).

7.5 Economical aspects of HHD

From a financial perspective, multiple studies have demonstrated in various countries that HHD is more cost effective than CHD, partly as a consequence of lower staffing and overhead costs as well as minimised transportation and infrastructure expenses20,23,24,25. As population of dialysis patients is growing and the financial burden of ESRD on global health systems steadily increases21, health care providers are looking to increase patient uptake to HHD programmes.

However, as some costs may transfer from the dialysis centre to the patient, this may be perceived by some patients as a barrier to HHD12.

Costs in addition to those incurred through the installation of dialysis machines and water purification systems include electricity and water usage, storage of dialysis consumables, room spared to setup dialysis chair, and machine, treatment sets and equipment for health monitoring, such as scales and blood pressure machines20. New portable machines require less utilities to operate at home than traditional machines and reverse osmosis water treatment. Two microcosting studies have shown a cost of € 112 per year for IHHD with these systems vs. € 544 with a traditional machine and € 1 138 for CHD24,25. In some countries private, public or charity allowances or discounts may be available for patients’ specific extra costs (e.g. allowance for care assistance, discount on energy bills, travel allocation, tax reduction…). Assistance with these costs through reimbursement schemes may function to minimise financial burden and sustain continued uptake to this modality.

Summary

This chapter has provided an overview of HHD, in terms of the lived experience for both patients and care partners. The flexible nature of HHD shifts away from the rigidity of CHD, and instills a sense of normality into patients’ lives. Nonetheless, the continued support of patients and caregivers, through regular nursing contact and peer networks, is fundamental to the success and expansion of HHD as a viable modality.

Learning Activity

- How might you recognise care partner burnout?

- What interventions could you employ to address this issue?

- How could you prevent this from happening in the future?

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge the patients who kindly told us their stories about living with HHD.

EDTNA/ERCA Secretariat

E-mail: secretariat@edtnaerca.org