Katey Atkins

Dr., MBBCh, MRCPUK, BSc (Hons), MRES

Research Fellow

Wessex Kidney Centre, UK

Katey.Atkins@porthosp.nhs.uk

Natalie Borman

Dr., MBBCh, MRCPUK, MRCPneph, PGDip, MD

Consultant Nephrologist

Wessex Kidney Centre, UKnatalie.borman@porthosp.nhs.uk

12.0 Home Programme Case Study

Learning Outcomes

- To determine factors that contribute to a successful Home HD programme

- To understand the importance of a designated Home HD (or Home therapies) team

- To learn about the value of education and awareness for all patients and staff

- To identify methods to ensure that patients are always at the centre of the programme

Introduction

The following chapter will outline the experience of the Wessex Kidney Centre, Portsmouth, UK in establishing and growing a large Home HD programme using the NxStage System One.

12.1. Background

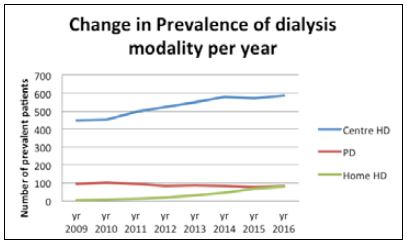

Wessex Kidney Centre (WKC) is located in Portsmouth on the south coast of England. It is a large renal centre with a population catchment area of 2.5 million people spread over a wide geographical area. The regional incidence of end stage renal disease (ESRD) and hence dialysis is growing in line with the rest of the United Kingdom (UK) and Europe1. WKC has an active and growing renal transplant programme, a large central haemodialysis (HD) unit, eight satellite HD units, and has sustained a large Peritoneal Dialysis (PD) programme even when many others were declining. However, like much of Europe Home Haemodialysis (HHD) declined during the late 1990’s2 and for a decade WKC had no HHD Programme at all. In 2009 WKC took action to re-established a HHD programme. It has since shown rapid growth and now sustains a large number of patients on HD at home. Figure 1 shows the change in prevalence across dialysis modalities in WKC.

In 2009 the percentage of all HD patients undertaking HHD was just 0.4% (HHD prevalent population). By 2016 this had increased dramatically to 10.4%. The following chapter will outline the successes of this programme and the key learning points.

12.2. Key drivers

The re-establishment of HHD in the WKC in 2009 had several key drivers.

In 2002 the UK National Institute for Clinical Excellence (NICE) concluded that all patients deemed suitable for HHD should be offered HHD. NICE also suggested that 15% of prevalent dialysis patients could be on HHD3.

Patients themselves were a prominent force in driving forward change. Aware of inequitable access to HHD dependent on their base renal unit they challenged WKC to improve the local situation.

The prevalence of patients on HHD in the UK in 2008 varied from 0% to 8% across centres4. As a unit without HHD provision prior to 2009, WKC was not meeting NICE recommendations or providing modality ‘choice’ to patients.

An additional driver was the increasing pressure on dialysis capacity within the UK. Many centres were struggling to meet the demand of a growing dialysis population, for which WKC was no exception. Large capital investment was not available so considering alternative methods to support service expansion was required. In 2008 the National Kidney Foundation released a policy statement that “Dialysis provision must be increased to cope with existing patient numbers and the growth in the number of patients predicted. Patients should be given a choice to receive their dialysis in hospital or at home”5.

Therefore, combining NICE recommendations, patients voicing wishes regarding choice and equality and dialysis capacity issues WKC embarked on a project to address these areas with the view to improve the service provided.

12.3. Establishing a HHD Programme

The initial attempts to re-establish HHD in WKC took place in 2004 when following a small financial investment two patients trained to use traditional machines at home, over a 3-month period. The first patient was transplanted 14 days after starting to dialyse at home, the second patient stopped as they felt it was too much for them, largely due to a lack of in house technical support6.

Undeterred by the early difficulties the team set about looking for alternative models. In 2009 the NxStage System One was launched in the UK and WKC viewed this as an option. It was essential that the therapy could be delivered within existing tariff and fit within the current staffing structure. WKC was able to negotiate a tariff price per treatment cost which included technical support and gained agreement to trial the machine in a single patient. Staff already employed within WKC took on the responsibility of managing this in addition to their usual job roles.

The pilot period culminated in data of the experience being presented to the Portsmouth Hospitals National Health Services (NHS) Trust board. Approval was given for a further five patients to join the HHD programme and appointed from a satellite unit to specifically manage this development.

12.4. Growing a HHD Programme

The Initial patients enrolled into the programme were considered to be medically stable and highly motivated, with good vascular access.

They would be fully independent without the need for a care partner. By 2011 confidence within the programme allowed for further expansion to include patients with more complex needs. The first patient transferred to nocturnal therapy and the first patient who lived alone was trained for HHD. The lead nurse role became a permanent post and a dialysis assistant was appointed to support her.

The programme continued to grow throughout the next 3 years. During this time an area in the main unit was established as the HHD training area, however this was not a dedicated sole use area and was also set up for bed spaces. Training was interrupted on multiple occasions due to demand on hospital beds. It became clear to the team that to facilitate continued programme growth a dedicated training area away from the inpatient unit was required. An area for this purpose was successfully secured. Despite measuring just 2.4 by 4.7 meters the team were able to rapidly expand their training abilities, training 45 patients during 2014. This area was increased in 2016 to a space 50% larger with the original area still available for use and storage (Figure 2).

HHD staffing numbers have also grown with the programme. There are no current national guidelines on the number of patients a Home HD nurse should support but it became very clear in the WKC programme that once that number exceeded 20 patients per nurse the patients reported feeling unsupported and there was a clear increase in patients stopping therapy for this reason. This evidence supported the successful application for financial support to employ more nurses with the aim to maintain the nurse to patient ratio below this level. This was to ensure adequate support for those established on HHD but also to allow additional staff to continue training. WKC has now set a limit of 15 patients to one nurse; with all Home HD nursing staff also being able train patients.

During 2014 the first patients trained were from pre-dialysis clinic and PD, supported with a tailored training plan. At this point in time all patients expressing an interest in HHD were visited at home by the dialysis assistant. This facilitated providing initial education with a home environment assessment. Home HD was also incorporated into the WKC pre-dialysis DVD which is given to all patients in the predialysis clinic. Educational and awareness events are regularly carried out in all satellite dialysis units to discuss home dialysis with both staff and patients to ensure that patients are aware of this options should they wish to consider it. In 2014 a service tender for HHD services was completed.

Growing the programme also meant thinking outside the box. Renal care overall is complicated by the logistics of living on an island 6km off the coast; the Isle of Wight (IOW). In 2015 a team of enthusiastic nurses working in the IOW satellite unit took on the role of training patients for HHD supported by the main HHD team so patients could remain close to home.

During 2016 the Home HD team set about mapping the patient journey from decision to independence at home. This has enhanced the smooth transition for all patients, streamlined the information given and the subsequent support of a patient once home. All patients were categorised via a traffic light system incorporating their level of medical complexity and support needed (by patients or carers). This has allowed staff to target resources to those who need it the most and highlight changes as patients move through the traffic light categories. In 2016 we took the opportunity to update all standard operating procedures.

As the programme expanded the complexities of patients grew and the team has even gained experience in HHD for patients with terminal diseases.

12.5. Staff training and education

Ensuring staff education and acceptance of HHD has been crucial to the establishment and growth of the programme. The initial set up involved a number of nursing staff from satellite dialysis centres. This meant that dissemination of information across the region occurred by discussion with their colleagues. Many of the nursing staff in the satellite centres were educated and engaged as the programme evolved. The HHD team ensured regular feedback and updates for clinical and managerial staff to maintain their interest and support.

Once the team appointed a lead nurse, liaison roles were formed to link the main HD unit and the other satellite centres. This was vital to ensure efficient communication, support for the patients wishing to do HHD and also to harbour interest from patients on standard HD. Engagement from the satellite units also meant that cannulation training could be provided prior to commencing HHD training reducing the burden and stress for patients.

Regular HHD awareness days take place in all dialysis centres in WKC educating staff and patients about HHD. HHD is now part of the renal course which many of the nursing staff complete and there is an established HHD nurse study day. HHD has been incorporated into the induction programme for both nursing staff and junior doctors, and features in the speciality registrars training days.

In addition to the dedicated HHD nurse team several nurses in the main unit are also trained to use the NxStage System One machine. These staff undergo competency based training for the NxStage system. A regular HHD slot available in the main dialysis centre supports patients for respite and has proven to be a successful initiative.

12.6. Patient education and training

Patient education is essential for programme growth. Following the initial pilot, the HHD team set out to ensure that all existing dialysis patients were now aware of this option, which they would not have been offered in the pre-dialysis setting. This took the shape of patient awareness days in the satellite units. Education of the pre-dialysis nursing teams and the clinicians also played a role in filtering the information to the patients. HHD was incorporated into the predialysis DVD which is given to all patients.

The team used media coverage to inform the general public hoping to reach as many individuals as possible. This included the local news, news paper, radio, social media and patient groups.

Existing HHD patients volunteered for peer support events and helped educate others sharing their experience. This has included ‘campervan events’ where patients have dialysed in a camper van at the hospital and satellite centre sites so others can come, watch how it is done and ask questions.

Patient training has been a great success in this programme and facilitated the rapid growth that has been seen. Where possible the team encourage patients to learn self cannulation prior to commencing HHD training. By undertaking this in a familiar environment with staff they often know well, at a pace they dictate, the stress and anxiety generated over learning this new skill is reduced.

Patients are trained for HHD in a designated area by the HHD nursing team. The HHD team adopt a ‘hands-off’ approach to training from day one. Patients’ being active in their training early on empowers them to take control of their own treatment under watchful supervision whist highlighting potential concerns / issues promptly. Where possible the team encourage the patient to learn the entire dialysis procedure rather than relying heavily on a care partner to reduce carer burden. The final two sessions take place in the patient’s home so they are comfortable in their home environment. Training times and outcomes are discussed in section 12.7.

12.7. Clinical outcomes

Clinical outcomes of the WKC HHD programme have been very good. Data has been analysed of the first 135 patients trained for HHD up to May 2016.

The demographics of this HHD population are mean age 51.4 years (Range 18 to 80 years); 66% male; and mean BMI 27.8 (Range 13.3 to 50.8). The mean Charlson Comorbidity Score7 was 4 (Range 2 to 10) and 17.9% had diabetes causing renal failure. The majority of patients (88%) were on in centre HD prior to training, 10.5% were pre-dialysis and 1.5% from Peritoneal Dialysis (PD).

Access type was 73.9% native Arterio-Venous Fistula (AVF), 19.4% Central Venous Catheter (CVC), and 6.7% PTFE Grafts; and the majority of patients use the button hole technique. Of those patients with a fistula 82% were self cannulating prior to commencing HHD training. The mean training time for all patients was 10.5 sessions (Range 6 to 33 sessions) to dialyse independently at home.

Training failure rates have been very low. Only 6% of patients did not complete training and just a further 1.6% dropped within 3 months for any reason other than renal transplantation. Therapy retention has been excellent with 50.8% of patients still on HHD.

Of those who have ceased HHD, 60.7% were for renal transplantation, 9.8% died and 29.5% were for other reasons including therapy burden, change in medical condition or access issues. Average time on HHD prior to dropout for any reason was 15.2 Months (Range 2 to 74 months).

Prescribing is individualised to the patients, their life style and medical needs. The majority of HHD patients at WKC dialyse 5 or 6 days a week with either 25L or 30L of dialysate fluid. There have been a number of patients who have transitioned to nocturnal therapy8. These patients dialyse alternate nights using 60L of fluid. We have seen a reduction in the use of anticoagulants with many of those on short frequent therapy not requiring any at all.

There has also been a notable reduction in blood pressure medication.

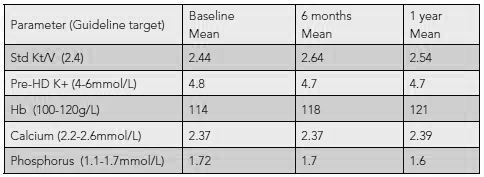

Data for the nocturnal patients has also been good, data for these patients is shown in Table 2, but the numbers of patients who have reached 1 year of nocturnal therapy are smaller at just 12 patients to date. The additional benefit of reduction in phosphate binders in nocturnal patients has also been noted.

Table 1: Shows the biochemical outcomes of the first 65 patients to complete 1 year on short frequent dialysis at home:

Table 2: HHD biochemical outcomes for nocturnal dialysis at baseline, 6 months and 1 year.

12.8. Successes and challenges

The WKC reintroduction of HHD has far exceeded even our own expectations. The programme has grown rapidly achieving short training times, excellent retention rates and good clinical outcomes.

The HHD team feel we have improved the quality of life of our patients by giving them an individualised therapy that fits their needs and allows more freedom. We have supported many of our patients to travel with their HHD machines further enhancing their experience. The WKC can now truly meet the NICE guideline that Home HD should be offered as an option to all patients deemed suitable. The WKC now has an enthusiastic dedicated HHD team providing everything from pre-home visits and education, training and community support.

There have been many challenges along the way especially with sourcing enough staff and training space for an extensive programme. The summary below will share with you the things we feel should be considered when embarking on a project like ours.

Summary

The team at WKC was one of the first European centres to set up an HHD Programme using the NxStage System One, developing a large programme in a short period. There have been learning points along the way that improve programme effectiveness. The key learning points are:

- A designated training area for Home HD with capacity for respite and review is essential to maintain programme growth.

- A designated Home HD (or home therapies) team is essential. The data from WKC suggest that no more than 20 patients per nurse but this should be reduced to 15 per nurse if they are also training patients.

- A clearly set out patient journey from expressing an interest to independent dialysis at home has been extremely helpful in ensuring smooth transition for patients.

- Education and awareness for all patients and staff, including satellite units, is very important.

- Early engagement with the Trust and managers is essential to ensure programmes are set up and supported correctly with the appropriate business cases in place.

- Above all ensuring that patients are always at the centre of all that we do and sharing the learning with them has proved exceptionally valuable to the ongoing development of our service.

Learning Activity

- How do you think some of these learnings at WKC could be applied to your HHD programme?

- How can you increase education and awareness in you centre?

EDTNA/ERCA Secretariat

E-mail: secretariat@edtnaerca.org