Carol Rhodes

RGN, Senior Sister, Renal Unit

Royal Derby Hospital, UK

carol.rhodes1@nhs.net

6.0 Education and Training in Home Haemodialysis

Learning Outcomes

- To understand the process involved in HHD training

- To highlight the specifics for training on a simple machine designed for HHD

- To provide a practical guide on how to implement a HHD training programme

Introduction

Training for HHD has historically been a lengthy process, taking up to 3 months in many centres. However, with the development of machines designed specifically for HHD, utilising new and simpler technology, this process has the potential to be much quicker and more accessible to patients. This in turn will enable a growth in the number of patients on HHD.

6.1 Logistics

There are key logistic steps in any training pathway. These should include:

- Referral for HHD training from pre-dialysis/dialysis unit/PD, or shared care to the HHD lead nurse.

- Home assessment performed by lead nurse/technician and arrangement of any engineer/plumbing work.

- Arrange training dates with patient and agree a provisional date for home.

- Order machine/supplies to be delivered to home address one week before training (or one week prior to discharge home).

- Arrange clinical waste removal once commenced at home.

- Organise electric/water payments through hospital/government (ifapplicable).

6.2 Checklist

6.2.1 Patient suitability

Once a patient has been referred for home training they should be assessed for suitability to perform dialysis at home and they must have agreed to do it. Primarily the patient should be physically and intellectually able and, most importantly, motivated to perform home HD and its related activities1. The patient and helper must be able to understand and retain information and instructions given. Related to this the patient and helper should be aware of the potential implications for changes in lifestyle.

General Physical Condition: The patient should be assessed for any general physical condition which may prevent him/her from carrying out his/her own treatment, i.e. poor eyesight, arthritis, etc. If so, the helper may be trained to carry out extra procedures. It would be preferable that the first patient has a good functioning fistula and should be physically stable on dialysis to start a programme but KIHDNEy cohort reported that any access is feasible at home and a wide range of patients may be suitable for HHD regardless of age, size (BMI) and commorbidities (Charlson score)6.

Moreover complex patients may specifically benefit from receiving more Frequent Home Haemodialysis (FHHD), e.g. improving blood pressure control and reducing the risk of intradialytic hypotension7,8 (see Chapter 3).

If units offer a shared care option (self-care in the dialysis unit) it will be easier to assess patient suitability. The transition from unit HD, to shared care, to HHD, can be a smooth process and can give staff valuable information on a patient’s ability to perform the necessary skills, and the patient valuable insight into self-care.

If shared care isn’t promoted it is important to try and spend some time with the patient whilst they attend for their regular dialysis sessions to assess some basic skills and requirements. It may be the carer that is going to perform the dialysis so this needs to be considered when assessing for suitability. The following guide can be used to assess each individual.

6.2.2 Consent

The patient and helper must be given sufficient information to allow them to make an informed decision to train on HHD. The patient should be willing to undertake frequent dialysis, but their treatment regime must be determined with them and taking their lifestyle into consideration. A signed consent may be asked.

6.2.3 Dialysis partner

Patients should be encouraged to manage their treatment at home as they will feel more in control of their life, but a trained care partner is required. Care partners may be a spouse, partner, family member (e.g. parent or sibling), or friend, and have various levels of involvement in the patient’s care. Some care partners may take full responsibility for all patient’s care, performing all aspects of HHD. Other care partners may only have a limited involvement in the HHD treatment such as cannulating an arterio-venous fistula, and removing the needles postdialysis, or assisting in case of issue.

6.2.4 Suitability of the home

The patient should have a suitable room which is large enough to house the dialysis machine and other equipment required for haemodialysis.

The location of the machine must be agreed with the patient and helper. Ensure a telephone is accessible in the house.

A home assessment should be performed using these criteria. More information about home suitability is available in Chapter 4: “Basics of Home Haemodialysis”.

6.3 Training

6.3.1 Cannulation training

If cannulation skills can be achieved prior to training the patients can concentrate on machine skills during HHD training. If a shared care programme is being used this is an ideal environment to prepare patients prior to home training and concentrate on cannulation skills. As part of patient advocacy, promotion of self-care and longevity of access, patients should be encouraged to self cannulate2. A cannulation education and competency pack should be used.

It is also possible for patients with tunnelled lines to go home, but it would be necessary to train a partner to perform the skills necessary for connection and disconnection.

6.3.2 Training schedule

NxStage has instructions to train on System One with a patient in 10 days. In Wessex Kidney Centre, Portsmouth UK, where 82% of patients are self-cannulating prior starting training on the machine, average training time is 10.5 days, (see Chapter 12).

In the KIHDNEy European cohort, overall training time was achieved in 18.9 sessions vs. 27.7 sessions in the FHN Nocturnal Trial on traditional machines6.

A training checklist can be agreed with the patient where they attend for up to 5 sessions per week for the two week training period. Ideally the patient has dialysis on the machine in a designated training area.

6.3.3 Training allocation

A member of the home haemodialysis team should be allocated as the trainer. This can be a support worker, or nurse depending on staffing available. Their is a worldwide concensus in PD programmes about a maximum ratio of 1 nurse for 20 patients. Wessex Kidney Centre (Portsmouth, UK) experience confirms this maximum 1/20 ratio and recommends a 1/15 ratio for HHD (see Chapter 12). An example of a two week training schedule is attached at the end of this chapter; this schedule is based on training using the NxStage machine. (Appendix 1)

6.3.4 Training location

Depending on the distance of the patient’s home to the hospital, if a designated training area is available in the hospital, and depending on availability of staffing, this can be done at home or in centre. Patients may feel more comfortable and concentrate more in their home environment or they may feel safer initially doing this in the hospital. If patient training happens in the renal unit, a dedicated area is highly recommended but can be just as small as the space to fit 1 home machine and 1 dialysis chair. This to prevent schedule conflicts with routine care or in-centre activity.

6.4 Training tools/curriculum

6.4.1 Adult learning

The principles of adult learning presume that adults are actively involved in the learning process. A training programme can be tailored to allow patients to learn using speeds and styles at which they feel comfortable1.One of the most used classifications of learning styles is one proposed by Flemming and Mills, 19923 the VAK model, this describes 3 main learning styles; visual, auditory and kinaesthetic learning. It is important that a training programme incorporates each of these styles which complement each other and can be adopted by the individuals depending on their own style or mindset with a specific topic to learn.

The trainer should assess the patient and/or carer prior to training to try and understand which their prefered learning style is. It is important to remember there are other learning styles and everyone may adopt their own unique style but memorisation may be limited to only 20% with “receiving” learning styles.

“Participating” teaching that includes demonstration, discussion and exercices may increase memorisation to 75%.

“Doing” teaching with coaching, repetition and verification of skills may allow optimal competence9.

6.4.2 Training support materials

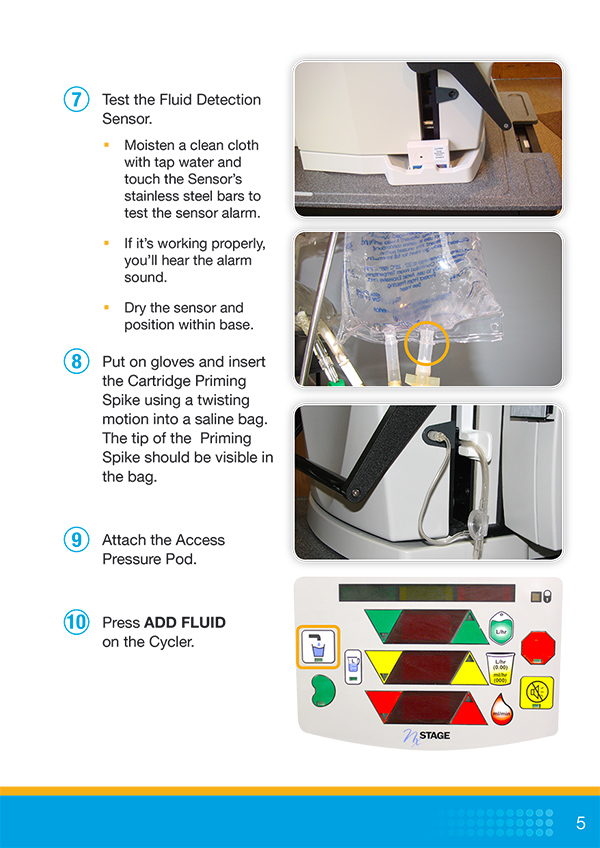

A training pack with all written information should be available, with quick guides and pictorial guides. A good start to any programme is the use of training aids that are strong visually, with step by step photography to demonstrate the dialysis procedure with a minimum amount of text1.

Demonstration videos are also useful for patients to watch on portable devices during their training. These can be accessed from home for reminders of various procedures and machine skills once they are independent at home.

6.4.3 Demonstration machines

During training it is useful to have a demonstration machine which patients/carers can practice on. This enables repetitive training each day on all stages of dialysis. It has been suggested that some sort of patient based simulation training may be helpful to validate patient’s readiness to begin HHD1.

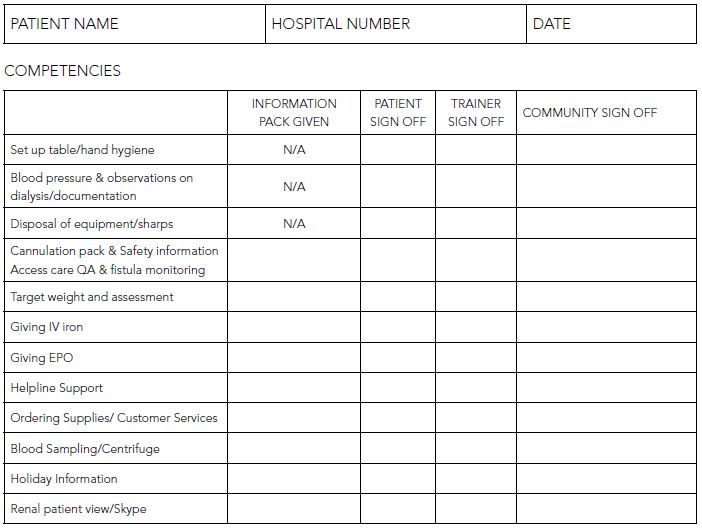

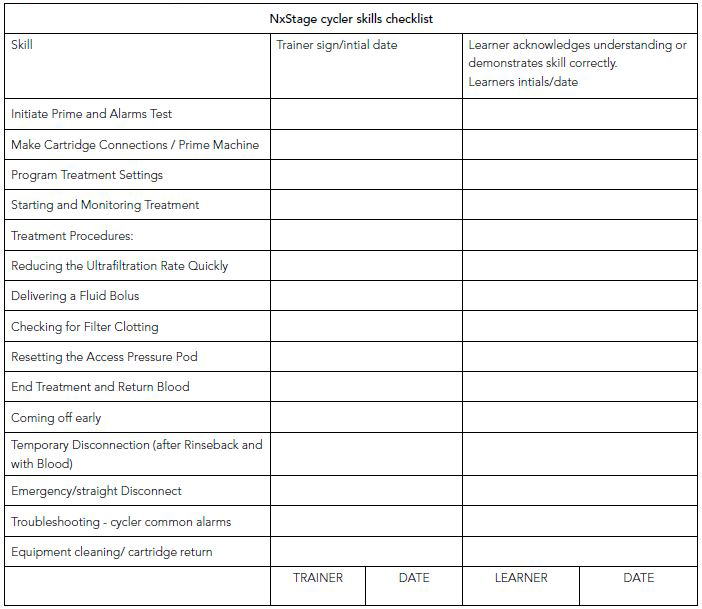

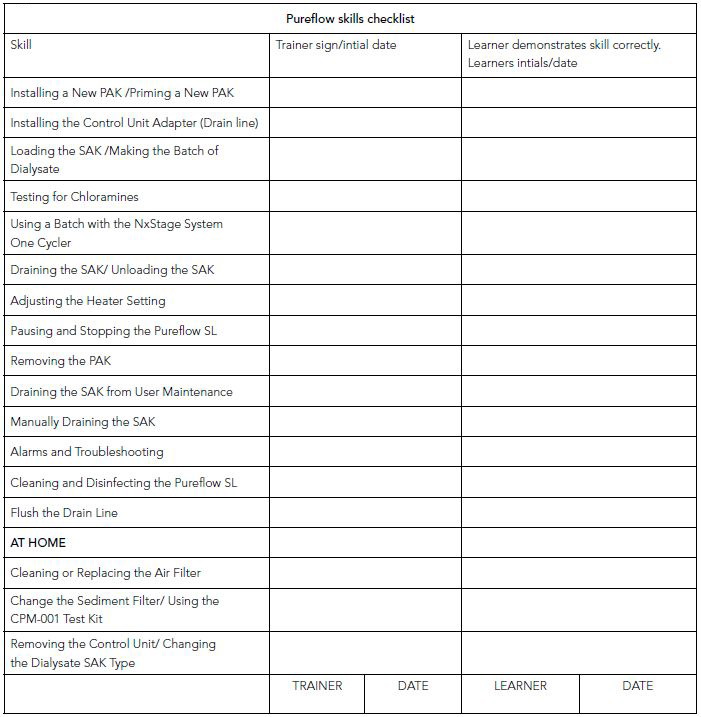

6.4.5 Competencies and follow-up

During training all competencies for machine and other skills need to be signed off by an allocated nurse and the patient. This is normally done towards the end of week 2. Examples of skills checklist can be found in Appendix 2, 3 and 4.

6.5 Going home and follow-up

6.5.1 Transition to home

Follow up is necessary for the first week at home for at least 3-4 dialysis sessions. During these the nurse may be present for the whole session. Once the patient is felt to be safe and confident the patient and carers can be left to undertake the sessions independently. During this initial period it is important to use communication links more frequently such as regular phone calls or Skype calls when performing dialysis. This allows advice and encouragement to be given to increase confidence.

6.5.2 Ongoing follow-up

All patients should then have a routine monthly visit for bloods, QA/ access monitoring, and general checks. Ideally visits should be during a dialysis session to assess cannulation technique and machine skills.

Key follow-up strategies include:

- A formal technique check should be done every 6 months. Retraining and assessments after being at home for a while or if problems are identified are good practice as people develop adaptations to what they have been taught.

- It is important clear guidance is available for patients at home, for them to understand their responsibilities and what the team can provide to assist them at home.

- A guide on who to contact in the event of a technical or medical issue should be readily available.

- A dialysis regime needs to be agreed and this needs to be recorded by the patient at each dialysis session.

- A designated nurse can be assigned to monitor and support each patient before they go home.

More detail on follow-up is provided in Chapter 8: “Ongoing Support”.

6.6 Risk reduction

6.6.1 Access

If patients are using a fistula, ideally a buttonhole or rope ladder technique will be taught. The use of 2% mupirocin ointment is recommended for all patients undergoing buttonhole technique4. If rope ladder technique is used patients need to ensure that the needle sites are rotated so that even distribution of puncture sites occurs along the length of the access2.

If patients are on a tunnelled line a 2 person technique should be used to minimise infection risk, an antimicrobial lock solution is recommended5.

More information on access and cannulation is provided in the specific Chapter 5: “Vascular Access for Home Haemodialysis (HHD)”.

6.6.2 Blood loss

One of the biggest risks of performing HHD is disconnection within the system or bleeding from fistulas. Reduction of this risk include the use of wetness detectors, good anchoring and secure taping strategies.

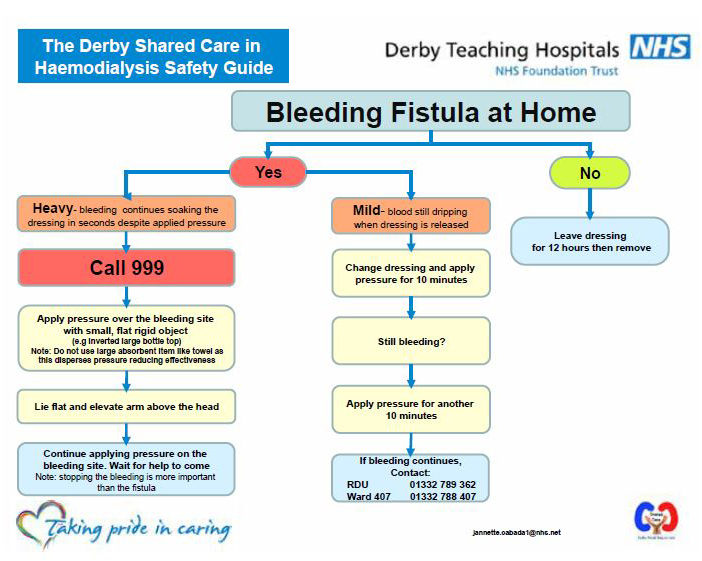

It is important for patients to recognise warning signs and take the appropriate response to any problems with their fistula. A safety guide has been developed for patients to use in shared care and at home, to minimise risk of bleeding from fistulas (Appendix 5).

Venous needle dislodgement is also discussed in Chapter 9: “Safety and Risk Management”.

Appendix 1 – 2 weeks training schedule (for NxStage Medical)

Alarms discussed this week

- ALARM 4 BLOOD PUMP OFF

- ALARM 7/8 ALARMS OVERIDDEN / PRESSURE LIMITS OPEN

- ALARM 11 ARTIERAL AIR

- ALARM 10 VENOUS AIR

- ALARM 24 ACCESS PRESSURE LOW

- ALARM 25 ACCESS PRESSURE POD ERROR

- ALARM 30 VENOUS PRESSURE HIGH

- ALARM 37/38 HIGH BALANCE CHAMBER ALARM

| Week 1 | Training topic |

|---|---|

| Day 1 | Patient is introduced to the various parts of the machine ie Pureflow, cycler, PAK, SAK etc Patient is shown how to prepare for treatment, line, prime and programme the machine. Patient is put onto dialysis and shown how to perform observations during dialysis and how to come off the machine. Patient is given a tablet/laptop with training videos and literature and shown how to access these. Patient is given the manuals for the NxStage device and made aware how this is useful for problem solving with their device. Patient is given the helpline number for technical problems once home and explanation given when to use this. |

| Day 2 | Patient prepares their own machine with support and goes onto dialysis. A demonstration is given with the training device, going through the process of lining, priming, connection, highlight key part connections etc. Patient is given tablet/laptop and guided through training videos/literature. |

| Day 3 | Patient prepares their own machine with support and goes onto dialysis. Assessment is made on how the patient is understanding and following instructions from the training book and following demonstration videos. |

| Day 4 | Patient prepares their own machine with support and goes onto dialysis. Introduce some troubleshooting alarms, air 10/11 alarms and pressure pod reset. |

| Day 5 | Patient prepares their own machine with support and goes onto dialysis. Introduce further troubleshooting, including weight loss minimum alarms 24,25,30,37,38 |

Alarms discussed this week

- ALARM 10 VENOUS AIR

- ALARM 11 ARTERAL AIR

- ALARM 40 RECOVERABLE POWER FAILURE

- ALARM 41 NONE RECOVERABLE POWER FAILURE

| Week 2 | Training topic |

|---|---|

| Day 6 | Patient performs all machine skills required each day for dialysis. Recap of everything from week 1. Go through alarms 10/11, weight loss minimum, and pressure pod reset. Power failure is simulated on training device to show what to do in a recoverable power failure (none recoverable power failure also discussed) |

| Day 7 | Go through vascular access module and competencies, including fistula safety guide. On tablet/laptop introduce to renal patient view / how to use Skype (a login can be made for patient on this day) |

| Day 8 | With community home dialysis nurse and trainer, install machine at home and demonstrate to the patient how the connections are made. Discuss common alarms and include temporary disconnect. Check bloods/demonstrate blood sampling technique. |

| Day 9 | Discuss alarms 10/11 unless patient is confident with these and temporary disconnect. Perform emergency washback simulation on training device. Sign off all competencies/checklist. |

| Day 10 | Discuss bleaching the waste line and general maintenance of the machine. Ensure the patient is ready to go home / arrange plan for home with community nurse. |

Appendix 2 – Sample skills checklist

Appendix 3 – NxStage cycler skills checklist

Appendix 4 – Pureflow skills checklist

Appendix 5 – Managing a bleeding fistula at home

Summary

HHD training programmes will vary depending on machine availability and choice, patient uptake, and staffing availability. Training curriculums and strategies to reduce risk are an important part of training.

Learning Activity

- How do you assess suitability for a patient to undertake HHD training?

- How do you implement a two week training schedule and what are the training tools required?

- What ongoing follow-up is required for patients on HHD?

Acknowledgements

Many thanks to Dr. Richard Fluck, Christopher Swan and Janette Cabada for their contribution to the text.

EDTNA/ERCA Secretariat

E-mail: secretariat@edtnaerca.org